The Scholar of Córdoba

Twelfth-century Andalusia was the nexus of a cosmopolitan world whose realities are little remembered today. Merchants sent their wares as far away as India. Caliphates ruled much of present-day northern Africa and southern Europe along the Mediterranean, overseeing societies where speaking more than one language and traveling by ship hundreds of miles was common for the educated classes. Córdoba itself had a golden age around 1000 CE:

Córdoba had a prosperous economy, with manufactured goods including leather, metal work, glazed tiles and textiles, and agricultural produce including a range of fruits, vegetables, herbs and spices, and materials such as cotton, flax and silk. It was also famous as a center of learning, home to over 80 libraries and institutions of learning, with knowledge of medicine, mathematics, astronomy, botany far exceeding the rest of Europe at the time. (source: Wikipedia)

It was into this bustling, globalized metropolis that the Jewish philosopher Maimonides was born circa 1135 CE. In addition to working as a personal physician to an Egyptian sultan and being well-trained as an experimental astronomer, Maimonides has an impact on contemporary education that might surprise you.

Even a millennium later, schools in Israel use a rule of thumb first proposed by Maimonides: a teacher can manage a classroom of up to 40, but then, halve the size. If you have 40 students, hire one teacher. 41? Divide the pupils into two classrooms of 20 and 21. As quoted in the The Quarterly Journal of Economics:

The importance of Maimonides’ rule for our purposes is that, since 1969, it has been used to determine the division of enrollment cohorts into classes in Israeli public schools. The maximum of 40 is well-known to school teachers and principals, and it is circulated annually in a set of standing orders from the Director General of the Education Ministry.

Classroom size in the U.S. is a hotly debated topic, with many arguments conflating correlation with causation. Regardless, 40 students in one room would be unusually large in an American classroom — we’ll get more into median statistics, but most classrooms are around 20-25 students. Israel, on the other hand, has an average of 27 students per class. This article will examine this debate, and raise the question: are we asking the wrong question? Is reducing class size the best use of state-level funds in the U.S.?

The One-Room Schoolhouse: Building a Mythos

Fast-forward a few hundred years and trudge north a few thousand kilometers. You’re now in the middle of nowhere in Norway. The year is 1739. If you can’t imagine it, basically imagine the rural portions of the Disney film Frozen. Brrrrr.

Just six years before, Christian VI, the king of Denmark and Norway, introduced the Stavnsbånd, a quasi-serfdom that forbade young men in Denmark between the age of 14 and 36 from leaving the estate on which they were born. Too many peasants had been trying their luck in the cities. Can’t start getting ideas! Norway proper had its own strict system of social stratification and splitting up of estates. The majority of Scandinavian emigrants to the Midwestern states of America came from this beleaguered social class.

So when a decree comes out from the King in 1739 that your children have to attend school, you would be forgiven for grumbling that you could use some extra hands on the quickly-dwindling farm before you’re called up to go fight in a war against Spain. Reciting the confirmation might have seemed tangential to the realities of your life. Only 1 in 5 men could sign their names in your region in 1720. But the traveling teachers seem insistent, so you let your child go get some book learning.

It was this almost accidental policy change that led to a shocking rise in literacy in Scandinavia. By 1800, almost all Norwegians were literate.

What does that have to do with the one room schoolhouse? A lot, it turns out. This form of instruction — imagine Little House on the Prairie, for the ‘70s TV fans — where students of multiple grade levels are all taught by one teacher, was by far the most common in the Midwestern states, where the realities of small, isolated rural communities and the cultural inheritance of the immigrants themselves meant this was a common, even iconic, form of instruction from about 1850 to the Second World War in the U.S. and Canada, especially in so-called flyover country. What was viewed as “normal” instruction — at home or out of the home, coed or single sex, religious or secular — varied greatly by region in the U.S. until the 1940s. Much of the Western world underwent programs of educational modernization whose effects can still be felt today.

Explosive growth and gradual decline in size of classrooms

Multiple trends converged to increase the average classroom size from 1850 to 1900. Child mortality, happily, fell dramatically, which contributed to the overall U.S. population more than tripling in that time span.

The United States rapidly industrialized — the nation went from 85% rural to just 60%, with a majority urban populace by 1920. And the U.S. was an early adopter of universal compulsory public education.

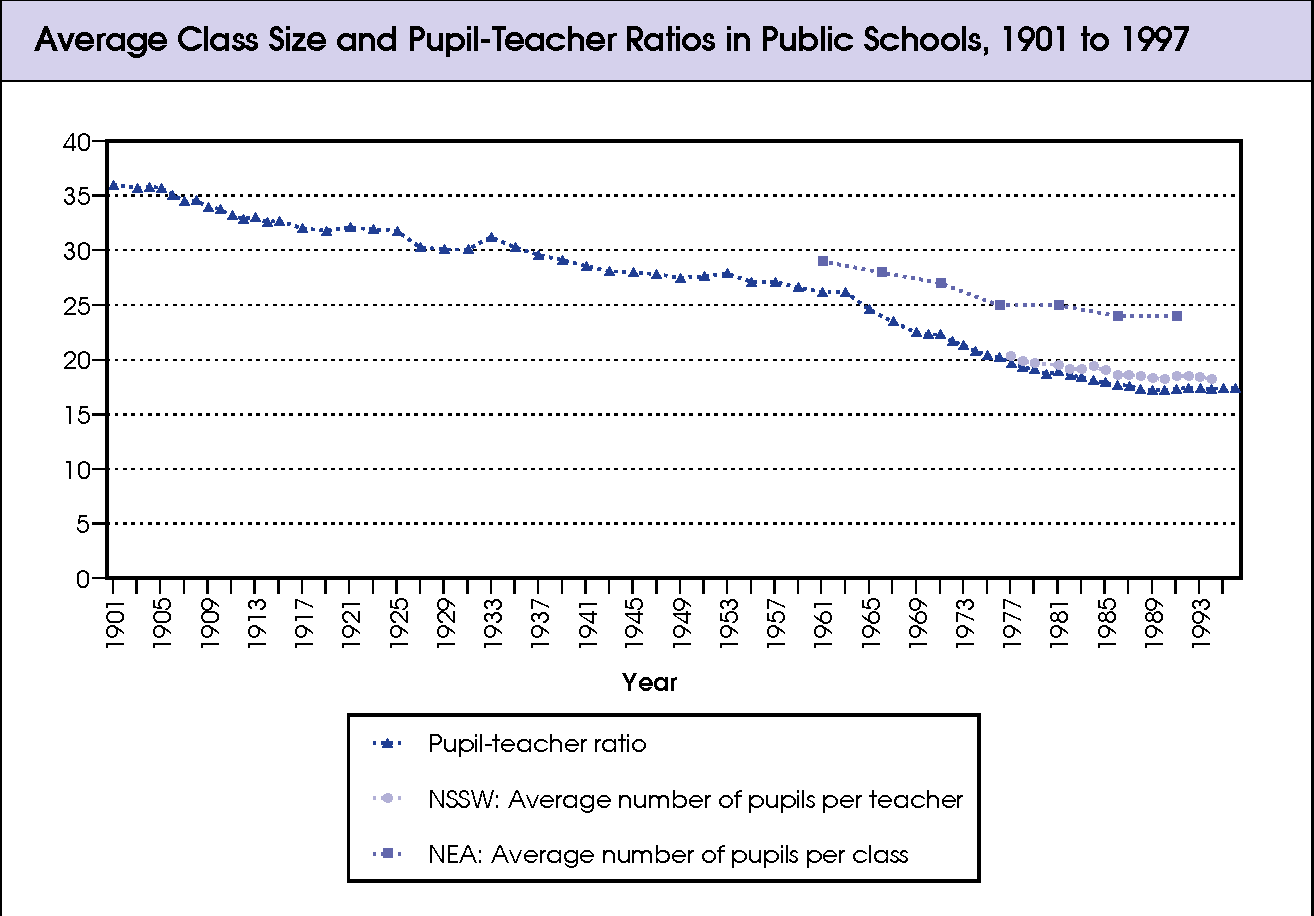

This led to huge classrooms by the turn of the 20th century. Classrooms of 50 weren’t unheard of in New York City, and the average size was 35 across the country. But Maimonides would get his wish: class size has steadily decreased since its peak.

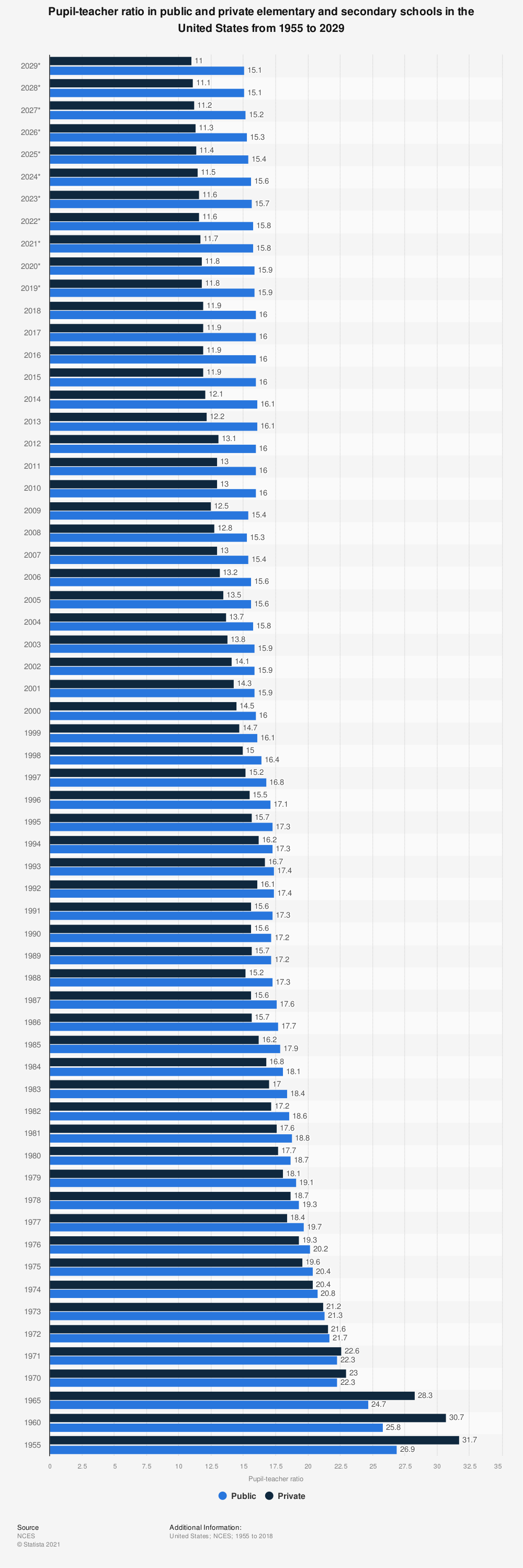

In the past thirty years and projecting into the future, this trend shows no sign of slowing down.

What are the reasons behind this decline?

One of the clearest is declining birth rates. With fewer children, classrooms will shrink unless they are consolidated. Another is mandates. More than half of states have laws limiting the number of students in homerooms in public schools.

Making a smaller class comes at a price — hiring more faculty. If you split your 40 students into two classrooms of 20 students, you must hire an additional teacher. Repeat that ad infinitum, and Classroom Size Reduction ends up being a costly educational reform — to the tune of billions of dollars, on par with Title I.

Are there any high quality studies that show that further reducing classroom size in the U.S. is worth the investment?

Are these mandates worth the investment?

STAR was an experiment in Tennessee in the late 1980s that was unique — it was well-designed, longitudinal, and introduced controls. Students were taught in regular-sized classrooms or dramatically reduced-size classes.

The upshot of the study is that you have to dramatically, not slightly, reduce class sizes to see lasting improvements in test scores. When it came to the reported income of the students once they reached adulthood, there was no clear benefit.

In other words, one question policymakers will have to grapple with is what are they hoping to achieve with reductions in classroom size. Better scores? Better behaved students? Better life outcomes? If you don’t know where you’re going, it doesn’t matter which path you take, to paraphrase one Cheshire cat.

A natural experiment, by no means a true control group, but a parallel track in the U.S. educational experience, is worth noting here and reflecting on.

An age-old model, on the rebound

Not discussed so far? Private, formally known as independent, schools. Until the universal education mandates of the 19th century, most formal education resembled home school or parochial school.

All evidence points to a privatization movement that is growing. Charter schools (publicly funded, but privately run) now comprise 7% of enrollment. About 10% of students are in independent schools.

What’s the picture on classroom size? Prep schools do indeed have smaller classroom sizes — in their glossy brochures, it’s often one of the first things they advertise. (This author, resident in the state with the largest classroom sizes, is an alumna of a high school that has a tiny 9:1 student-teacher ratio.) Charters, on the other hand, are much more variable, but often have comparable classroom sizes to publics, if not slightly larger.

So what's the cause, and what's the effect? COVID disruptions heavily impacted education in every area and type of school in the U.S. — but urban school districts were hit harder by every measure than suburban schools where students could more easily isolate and learn remotely. Many parents who could pull their children from public schooling, did. Enrollments are indisputably up outside the public education system.

But do students at independent schools — especially top-ranked, ultra-competitive, eye-poppingly expensive elite schools — perform better on standardized tests, go to better-ranked colleges, and earn higher incomes as adults BECAUSE their classrooms were smaller … or was it more like correlated with other factors in their lives, such as parental income and education, safety of their home ZIP codes, and intangible expectations of their social set?

Basically, how can educational researchers control for the most fickle of variables: luck?

No magic wand: modest proposals for thinking about class size

The research seems to most clearly indicate that you get the best bang for your buck in classroom interventions at the earliest ages. Restaging a STAR-like study with true experimental conditions would be an excellent way to gather data about small versus medium sized classrooms.

Regardless, this debate often devolves into caricatures — as if the only options are the crowded conditions of a 1901 tenement school battling cholera and a rosy picture of your child contemplating the Decameron in the Italian in a five-person seminar while gently cradling a lacrosse stick on their way to the Ivy League.

Reality rarely resembles these extremes — and it’s worth acknowledging that U.S. class sizes are about average among OECD countries. Some systems have very large classrooms, such as China and Korea, and see high test score results. Countries as different as Bangladesh and the Netherlands see private school enrollment rates above 80% — others, such as Cuba and Finland, have virtually zero private schools, and completely different social systems and outcomes.

In other words, we might want to borrow some wisdom from Maimonides again, and admit that at the moment, we need more information about the “ideal” classroom size before drawing sweeping conclusions:

Teach thy tongue to say 'I do not know,' and thou shalt progress. -Maimonides